More than the sum of its parts -- splitting requirements

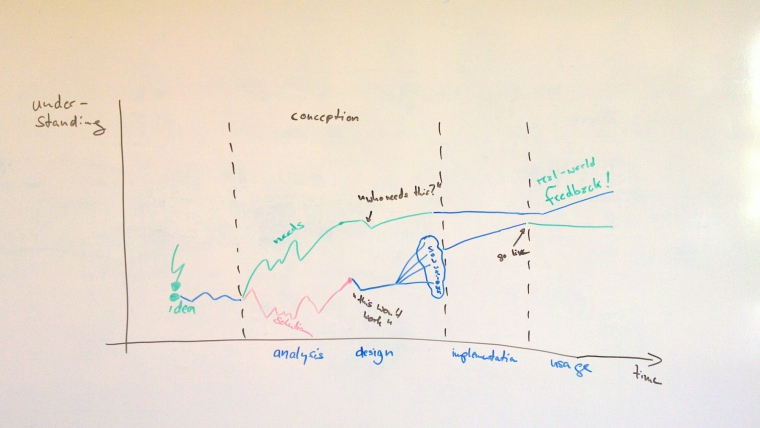

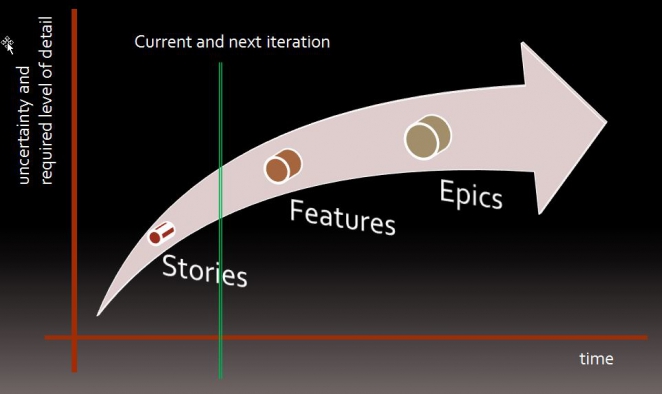

In the last article on the right size of a user story, I discussed some aspects that contribute to finding an answer that works in your context: clarity, functionality and effort. In this post, I want to discuss the question on how you can move from a big feature to smaller stories. The assumption here is that we already understand the requirements “good enough” (i.e. maybe captured in a use case document), so we have reached already a quite clear picture of what needs to be done.

There is quite bit of literature on these questions, with the book “Agile software requirements” from Dean Leffingwell being one particular source of input (the SAFe page on stories lists an overview). Being asked, what would you recommend, the usual consultant answer would be “it depends”, but I think it is safe to come up with some rules of thumbs.

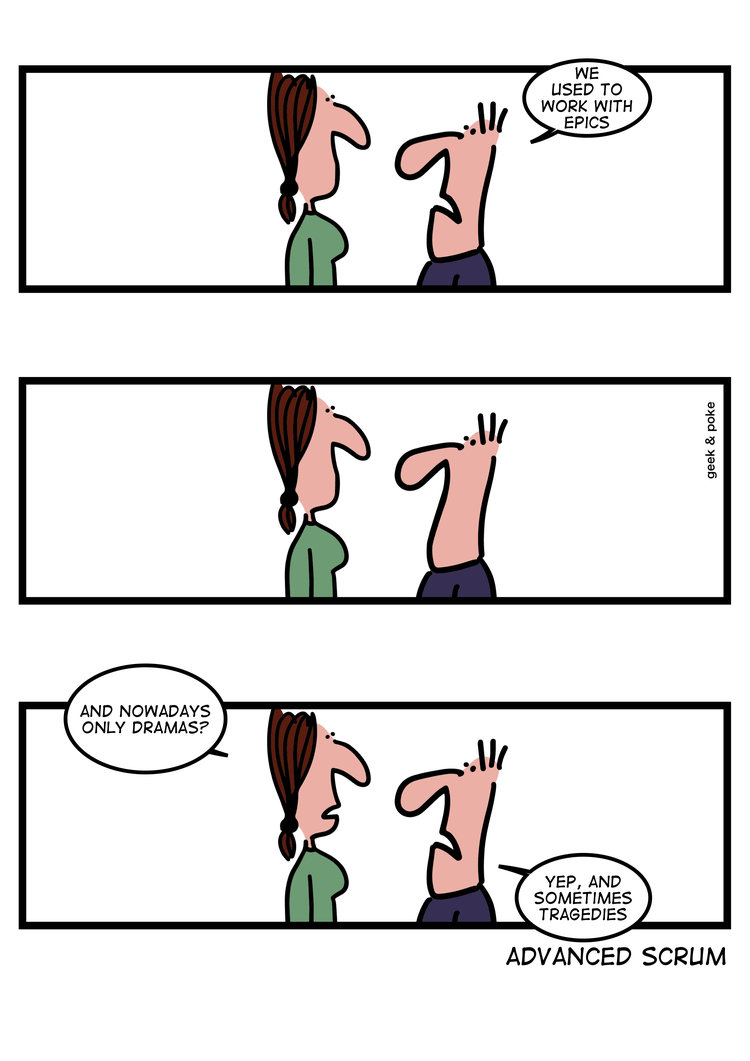

0. Don’t split

The bottom line for story splitting is that you should avoid it if you can. Having a lot of very small stories will come at a price — loss of overview is an important one, and if taken too far, it can also become hard to reason about the business value of a story. Formulating the “… in order to” part of the classical user story template (“As a <role>, I want <action> in order to reach <my goal>”) is often a good sanity check: if you have a hard time finding the wording for “my goal” is usual a sign that you’ve split up the requirement too much. There is one classical mistake that can easily result in this situation: if you break down a requirement by components or systems, it’s highly likely you will end up with problems to formulate a reasonable business goal — most probably you split off an implementation task, cf. below.

Assuming the main reason is to fit the work into one iteration (or one week of the iteration, cf. above), if your story is already “small enough” in terms of effort, then there is not much point in going for even smaller stories. You will run into the occasional discussion that a story should ideally be able to finish (“move to done”) within one day, but it should be up to the team to decide whether pushing for this really brings any benefits like additional helpful feedback. More often than not, the team might just try to game numbers, e.g. the number of stories they can finish. There is an obvious tension here between the benefits of small stories (delivering working code early, enabling quick feedback) and unnecessary overhead (splitting in a meaningful way, documenting, managing and tracking the bigger amount of stories), that needs to be balanced according to the situation at hand, but try hard to avoid splitting into too tiny details.

The other question is, do you need to split the requirement now? If the requirement does not need to be elaborated now, because it is not planned for the current or the next iteration, there is no need to split it now — potentially this requirement could change over time anyway, so preliminarily driving for details might actually cause more problems than help. For instance, when a bigger feature involves multiple workflow steps and you split the feature into stories, where each implements one step at a time, you might have a hard time in your backlog tying these pieces / steps together, if you want to revamp these steps in its entirety.

1. Do the minimal thing first

If you think you need to split down a requirement, try to identify the “minimal viable functionality” as the first story. This is the minimum functionality that the system needs to provide that brings some (potentially rather minimal) benefit to the user. This functionality becomes the first story, whereas all other aspects of the requirements are addressed (as extensions) in separate stories.

Foto assumed to be by Pavel Krok~commonswiki under [CC BY-SA 2.5], via [Wikimedia Commons]

As an example, let’s again think about user preferences for some system: the minimum useful functionality for a user consists probably of setting the preferences, saving, loading and applying them. Simple counting these steps leads you to the observation that this alone consists of at least four different functionalities. However, exporting my preferences to a file and importing them on a separate system is certainly not “minimal”. Depending on the intended users, even providing an inline editor to set the preferences might not be part of the minimum functionality. These functionalities could become separate user stories. The drawback of using this approach is that the resulting stories are not truly independent any more: you cannot prioritize exporting and importing preferences to be done before setting, saving and loading them.

Now, of course, this minimal viable functionality might still consist of a lot of work which might still be “too big” (in implementation effort, not fitting into one iteration). Here all the ideas from Dean Leffingwell are applicable, in particular trying to split by persona or business rule variations, data entry methods or data variations or workflow steps. In our example, setting preferences and saving as well as loading and applying preferences could be two different workflow steps (and hence different stories). However, this approach would probably result in stories that are too small according to rule of thumb 0 above. When splitting by workflow steps, try to have a minimal complete workflow in one story or at least plan to have this minimal workflow implemented in one iteration.

2. Optimize later

A good guiding principle in programming is to avoid premature optimization. While the principle talks mostly about optimizing performance of computations, we can also use it as a rule of thumbs for splitting requirements. The idea is to to take the simplest approach that could possibly work. This has a rather broad applicability in terms of technical aspects (architecture), but also usability and other so-called quality or non-functional requirements. After implementing this first rough version, use the feedback to check if it is “good enough” — e.g., whether performance, usability or security requirements are met already. If not, optimize these “-ilities” later on.

Some people might find this suggestion offensive. Security, for instance, is one quality that many claim cannot be designed into a system as an afterthought. But this is also not what I’m suggesting. Instead, I’m suggesting to formulate these “-ilities” requirements separately to isolate the functional core of the big requirement and to implement the optimizations later. This is quite independent of the need to design them — whether you design them upfront (as this might be part of your constraints in a “Definiton of ready”) or within a Sprint is a different question, but of course you need to think about the required qualities that the functionality needs to have. The idea here is simple: If your story is too big, put the proverbial lipstick on the pig in the next round. If you are afraid that your product owner will not care about security and will lower the priority of implementing these security stories to the point that they will never be implemented, your product has a bigger problem anyway (and probably security problems already) or the usage scenario that the product owner has in mind might be different from your expectation. Probably in both cases spelling out the required quality (and the accompanying work and effort) in a separate story could even be helpful to spawn a discussion.

That being said, breaking down your stories by functionality should be preferred. This is especially true if your stakeholders have some expectation of these qualities — if you miss out on these qualities, you’ll likely receive feedback to that effect. At least, you’ll be able to point to another story then to address it. Again, finding a good balance is important, but also not always easy.

3. Avoid splitting by technical components

By BrokenSphere (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY 3.0 ], via [Wikimedia Commons]

Technical user stories that are intended to cover work specific to some component are an anti-pattern. Typically they are brought up by people which are still stuck in the old trap to split work according to responsibility for features vs. components, cf. the discussion of features and components in SAFe. Don’t split by technical components unless the component can deliver business value / user functionality on its own.

Typically you cannot test some functionality in a reasonable way for some component on its own (e.g. the UI alone, not connected to the database). Hence, you will also not be able to get any feedback for the implementation of the story. E.g., saving and loading your preferences from the database is certainly a reasonable technical task, but how would your stakeholder test this without the UI being implemented? How would your product owner find out that there is a minor problem in the saved data if the only way to access it requires sending a web service request or proficiency in your programming language of choice? So, even though you might have finished the work on the component completely, you will not get the quick feedback that we would like to enable with small stories. And, of course, the component alone will also not be delivered as a result of your iteration, so it’s also not adding any business value at this point either.

This rule of thumb also can be debated. There are situations where one component can provide value already — e.g. a CMS system where you extend some functionality on the authoring environment first, so the editors can easily start using it. Even if the readers cannot yet see the result of the new features, some business value might already come from easing the work the editors. This case should not be confused with a different line of reasoning: For the UX designer, for instance, it might make a lot of sense to provide feedback on a UI preview that is not connected to the database. Your DB admin might already point out problems with the schema etc. However, this is inter-team feedback then, not customer feedback. In the end, the measure of progress in agile projects is delivering working software to the customer — and from a user perspective, both of these examples fall short, as essential functionality is missing. Instead, go back to rule 1 and try to identify the minimal complete slice of functionality that delivers value to the customer.

Task splitting and Spikes

There is, however, of course also a time when it is exactly the right thing to do to break down a story into technical tasks that need to be finished: this happens when the story is ready and due to be worked on given its priority, typically as part of a Sprint Planning 2 meeting in a Scrum setup. Especially for engineers it is easy to fall into the trap to confuse story splitting (as requirement work upfront) with task splitting (organization of concrete work within a sprint). A focus on technological considerations (and often also personal priorities) can quickly lead to splitting work such that it is developer-friendly, but does not deliver results to customers quickly. Let’s discuss some aspects of how task splitting influences work organization.

Stating the obvious, splitting technical work into tasks requires technical understanding, both of the system in which the requirement is implemented and of the technologies involved. But it is also not always the case that the team understands the system or the technology well enough. In this case, the team can decide to spend some time on research work to figure out what exactly needs to be done. Don’t define this as a “research implementation” task and plan to complete the entire story, you likely have no idea how much work it takes to complete everything anyway. Instead treat the research work separately, this is usually called a spike. As the goal of a spike is to learn something and not everything, a strict timebox should be defined (usually not exceeding one or two days), after which the spike is called of, regardless of how much insight was generated. Spikes usually are hence not estimated in story points, but reduce the capacity of the team, so you should also try to not have more than or two spikes per iteration.

By OSU Special Collections & Archives, via [Wikimedia Commons}

Splitting a story into tasks follows different rules: for instance, splitting by components is usually a good idea, especially if your team does not consist only of full-stack developers. Also, even with full-stack developers, you need to start somewhere, which good software architecture practices would demand to be clarifying interfaces between the various components. Which brings us to one big issue of task splitting: Identifying dependencies between tasks. These are usually directly following from the organization of the components. Of course, as with user stories, you should strive to avoid dependencies in the first place (and use dependency injection and other mechanisms to decouple your dependencies). This is not only good engineering practice, but also allows to parallelize the resulting work (i.e. have multiple people work on the same story). Teams sometimes split their work such that only one developer is actively working on a story that consists of multiple tasks. This usually leads to the situation that many stories are started but they all take a long while to be completed. Instead try to distribute work between multiple people: the frontend ninja can start his JS foo, while the backend expert whacks the database in parallel, modifying the previously defined contract as required during the work. If the team can work on multiple tasks of a story in parallel, then this does not only encourage collaboration and team spirit, it will also ensure that the highest priority work items are finished first.

But the tasks to complete a story usually also involves other work besides coding, e.g. UX work or manual exploratory testing. More often than not, these are not happening as agile “on the spot” as other work, instead it’s a quite common anti-pattern to treat an iteration like a mini waterfall: UX (of everything) happens at the start, then development, testing (of everything) happens at the end. This can lead to a lot of unneccessary work done upfront (UX for stories which the team actually doesn’t get around to) or too late (testing starts so late it cannot be completed in the Sprint). Again, try to do the work only when it is necessary and try to do more stuff in parallel.